Company of the Month: Urbahn Architects at 80: new generation of leadership continues legacy of problem-solving and innovation through design

Photo credit: Edward Caruso

New York, NY When Maximillian Otto Urbahn founded his eponymous architectural practice in 1945, the world was reordering itself after a global conflict. Cities needed rebuilding, institutions required reimagining, and America stood at the threshold of unprecedented growth. Eight decades later, the firm that bears his name continues to approach architecture not as just monument making, but as rigorous problem-solving that prioritizes functionality, efficiency and human experience over purely stylistic preoccupations.

Now ranked as the 79th largest architecture firm in the U.S., with ongoing projects valued at more than $4 billion, the practice is guided by four principals as well as a newly added leadership team of eight associate principals, who collectively embody the firm’s commitment to diversity of perspective and design excellence.

This leadership evolution comes as Urbahn’s work spans increasingly varied markets — from New York City subway accessibility retrofits to humane justice facilities, healthcare education centers in the Bronx and hotels in the Caribbean and Southeast Asia. What unites these diverse projects is a clear and consistent approach: maximizing positive impact on society within real-world constraints. This philosophy, embedded in the firm since Max Urbahn’s earliest commissions, values in-depth analysis, attention to human experience and timeless aesthetic over design trends of the moment or theoretical purity.

Ijeoma Iheanacho, AIA, LEED AP, NOMA and Enrico Kurniawan, AIA, NOMA; principal Natale Barranco, AIA, LEED AP;

assoc. principal Bridgette Van Sloun, AIA, CPHC, WELL AP; managing principal Donald Henry Jr., AIA, LEED AP, CPHC; principal

Rafael Stein, AIA; and Assoc. principals Daniel Kohn, AIA, LEED AP, Lawrence Gutterman, AIA, DBIA, LEED AP and Christopher Young, AIA. Not pictured is Nandini Sengupta, Assoc. AIA, LEED AP, NOMA.

Photo credit: Urbahn Architects

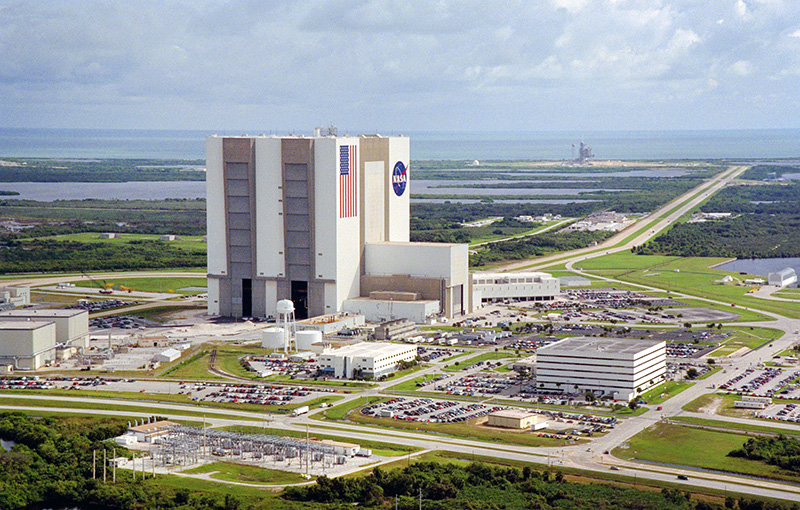

One early example of this approach came in 1962, when architect Martin D. “Marty” Stein was designing facilities for NASA’s Apollo program. While working on the tunnel system connecting various buildings, he made two seemingly minor decisions: leaving space beneath floors and positioning concrete tunnel blocks with openings exposed and aligned to create a cabling pathway. These choices weren’t driven by aesthetics, but by practical considerations that, as it happened, proved remarkably valuable decades later when NASA’s Mars mission needed to install advanced wiring systems that couldn’t have been envisioned during the early Space Age.

The Inheritance of Foresight

Max Urbahn established a foundation where technical excellence and functional integrity took precedence over an aesthetic agenda. His early commissions — educational institutions and research facilities — required deep understanding of specialized needs, establishing a culture where asking the right questions was the premise for successful design solutions.

“Our work is never formulaic,” said Donald Henry Jr., managing principal at Urbahn. “Each project deserves a truly in-depth analysis of desired functions, zoning and technical restrictions, budgets and architectural context.” In a profession that often celebrates grand spatial gestures, this commitment to pragmatism may seem understated. Yet over eight decades, Urbahn has demonstrated how this approach can transform public spaces, educational and healthcare facilities or transportation infrastructure in ways that enable meaningful impact on daily life.

As the firm looks to the future, this ethos of thoughtful problem-solving continues under the firm’s expanded leadership. With Urbahn celebrating its 80th anniversary this year, eight professionals were recently promoted to associate principal from within the firm: Bridgette Van Sloun, AIA, CPHC, WELL AP; Christopher Young, RA; Daniel Kohn, AIA, LEED AP; Enrico Kurniawan, AIA, NOMA; Ijeoma D. Iheanacho, AIA, LEED AP, NOMA; Lawrence Gutterman, AIA, DBIA, LEED AP; Nandini Sengupta, Assoc. AIA, LEED AP, NOMA and Ryan Bieber, AIA, LEED AP. This diverse group brings perspectives from varied cultural and career backgrounds, having worked across healthcare, sciences, public safety, governmental facilities, transportation, hospitality and multifamily housing markets. Their expertise informs the firm’s increasingly global practice.

The Architecture of Necessity

In the early 1990s, as digital technologies and new construction techniques were beginning to expand the possibilities of architecture, Urbahn took a conscious path. “We shifted our focus to projects with the maximum potential positive impact on the highest number of individuals,” said Rafael Stein, AIA, a firm principal. This wasn’t merely a business decision, but an ethical stance: architecture as a public service, rather than just aesthetic statement-making.

This philosophy manifests itself notably in the firm’s extensive work with the Metropolitan Transit Authority. As one of the most prolific lead designers within the MTA’s Fast Forward initiative, Urbahn has developed feasibility studies for nearly 100 of the system’s 472 stations and designed numerous accessibility retrofits to accommodate differently abled riders.

Natale Barranco, AIA, LEED AP, one of the firm’s principals, articulates the underlying mission: “Making subway stations more accessible and easier to traverse is key to improving the quality of life for the greatest number of citizens.” The primary goal, he explained, is enabling people of varying ability to reach platforms stigma-free without incurring prohibitively high costs or negative impacts on the surrounding community.

These transit projects exemplify how Urbahn translates its founding principles into contemporary practice. Each retrofit represents not just technical problem-solving, but a democratic vision of public space — one that extends Max Urbahn’s original belief that architecture should serve diverse human needs rather than architectural fashion. The recently completed $300 million renovation of the 14th St./6th Ave. complex stands as one of the most significant examples of this work.

Innovation Within Constraints

Perhaps counter-intuitively, Urbahn has found that tight constraints can often spark the most innovative solutions. Consider the Jersey City Municipal Services Complex, a 147,000 s/f campus built on a challenging brownfield site with existing industrial structures. Rather than clearing the slate through total demolition, Urbahn preserved and repurposed the remaining structural steel frames, integrating some of them into a new garage building and utilizing others to support shade structures and photovoltaic panels.

.jpg)

This adaptive reuse strategy wasn’t simply an aesthetic choice or to score sustainability points; it represented a pragmatic response to a limited budget, ultimately yielding novel environmental benefits. The result is a municipal complex that embodies efficiency and functionality, while maintaining visual coherence.

Similarly innovative was Urbahn’s pioneering of the design-build delivery model into New York City’s public contracting process. The Queens community space and parking garage, the city’s first major design-build municipal project, serves as a milestone for how public projects can be conceptualized and successfully carried out.

“We believe that every design must be buildable–from both financial and technical perspectives,” said Ranabir Sengupta, another of the firm’s principals. “Maintaining collaborative and positive relationships with builders, engineers and clients is critical to meeting project goals, schedules and budgets.” This emphasis on collaboration rather than architectural autonomy challenges the traditional image of the architect as the sole visionary, instead positioning design as one element within a complex ecosystem of considerations.

Photo credit: Ola Wilk

Designing for Human Experience

While much of Urbahn’s work is informed by systemic thinking, the human experience remains central to their design process. This is particularly evident in the recently completed CUNY Lehman College Nursing Education, Research and Practice Center in the Bronx – a $95 million, 52,000 s/f facility addressing the critical healthcare worker shortage in an underserved area.

The NERPC presented multiple challenges: building on a tight site footprint, designing sophisticated medical teaching facilities within a defined budget, visually incorporating a new building into a varied architectural context of an existing campus and creating spaces for students learning to navigate life and death decision making. Rather than focusing exclusively on technical requirements, the design team considered the emotional and often stressful dimensions of nursing education, and how architecture could support students developing the resilience and compassion central to careers in healthcare.

This attention to human needs within an institutional setting recently earned the project the American Institute of Architects New York Chapter’s 2025 Excelsior Award, recognizing both design excellence and social impact. The honor exemplifies Urbahn’s ability to work within strict parameters: budget constraints, site challenges, and complex technical requirements – all while maintaining a sensitivity to the experience of the building’s end users.

Global Reach with Local Sensibilities

The establishment of Urbahn International in Jakarta, Indonesia serves the firm’s clients throughout Southeast Asia. Current international projects include Sanur Wellness Village, a 21-acre healthcare resort on Bali, a master plan for the University of Indonesia Mandiri’s satellite campus in Lampung, the Mota House Hotel in Atambura and an athletic complex in Mampang.

Urbahn has also joined development teams as both architect and equity partner for several hotels in the Caribbean, including the 154-key Four Points by Sheraton at Trinidad’s Piarco International Airport and two in Georgetown, Guyana: a 140-key Cheddi Jagan Airport Marriott Courtyard and the 160-key Marriott Ecotourism Resort where the Demerara River meets the Atlantic Ocean.

The Continuity of Problem-Solving

Looking at Urbahn’s portfolio across eight decades reveals a through-line of practical innovation, from early work such as the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois to current projects like the design of facilities for New York City’s Borough-Based Jails initiative, which centers on fostering safety and well-being for both staff and the incarcerated.

These correctional facilities represent Urbahn’s approach in perhaps its most challenging application - creating environments that balance security requirements with spaces that support rehabilitation and human dignity. Rather than merely warehousing people, these designs reflect the belief that even the most utilitarian buildings can and should serve broader social purposes.

A notable project from the past, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board Building in Washington, DC, highlights the firm’s history of anticipating future needs. Completed in 1977, the 250,000 s/f government office building focused on energy conservation and flexible workplace design decades before sustainability and open office concepts became industry standards.

The Lincoln Medical Center in the Bronx, built in the early 1970s and home to the nation’s busiest emergency department, stands as another example of Urbahn’s roots in designing highly functional spaces for critical services. Similarly, the firm’s forward-thinking healthcare and public service projects in Africa, focused on improving access to vital governmental and healthcare facilities in Somalia, Uganda and Nigeria, demonstrate how architectural problem-solving can positively address fundamental human needs.

Beyond Building Design

When reflecting on both Urbahn’s past and its future direction, Marty Stein, who is still contributing his planning and design talent after 63 years of service to the firm, articulates a vision that extends beyond the traditional notions of architectural practice: “I believe architects can and should be more than just designers of buildings. They should play an important role in the development and improvement of services, such as healthcare, scientific research, refuse collection and mass transportation.”

This perspective positions architecture not as a transformative force in itself, but as a methodology for enabling and supporting positive social change. It suggests the quiet innovations that defined Urbahn’s early work, like those concrete block cabling pathways at Cape Canaveral, could serve as a model for how design thinking can create lasting value by anticipating needs that building developers may not yet recognize.

As Urbahn continues to evolve, this foundational ethos remains intact. The firm’s current work on the Royal Thai Consulate General renovation in New York City and accessibility upgrades at the historic Grand Inna Bali Beach Hotel demonstrates continued commitment to improving existing systems over imposing entirely new visions.

In an architectural culture that often celebrates novelty and spectacle, Urbahn’s eight decades of thoughtful problem-solving offers an alternative model of design excellence, defined by the enduring utility of spaces designed with foresight, technical rigor, empathy and delight. It suggests that sometimes the most profound architectural contributions are the ones that remain invisible until they’re needed, like space beneath the floor, waiting for the future to arrive.

“Although beautiful and inspiring buildings are important,” Stein said, “we have a responsibility to be part of this greater continuum, where we can contribute our puzzle-solving skills to help improve the state of the world.”